The prospect of a film presenting a select few of the many interpretations of Stanley Kubrick’s The Shining (1980) sounds like a great one to me. Being a colossal fan of the late director’s work, and of the “masterpiece of modern horror”2 in particular, I approached the film thinking, “Oh bliss… bliss and heaven. Oh, it (will be) gorgeousness and gorgeosity made flesh”.3 Surprisingly, at no other time in recent memory had I wanted more for a film to be over with––something I didn’t think I’d be saying, especially after a similarly recent viewing of Baz Luhrmann’s The Great Gatsby (2013). These instances are purely matters of taste, though. And what now differentiates the two films in my mind is that I’ve suspended judgment of Gatsby, since I haven’t committed myself to being critical about it––where the reasons and arguments come about “real horrorshow”4 and the like. But in the case of Room 237, I’ve attempted to turn a matter of taste into a matter of criticism. So here we go…

Hieroglyphics:

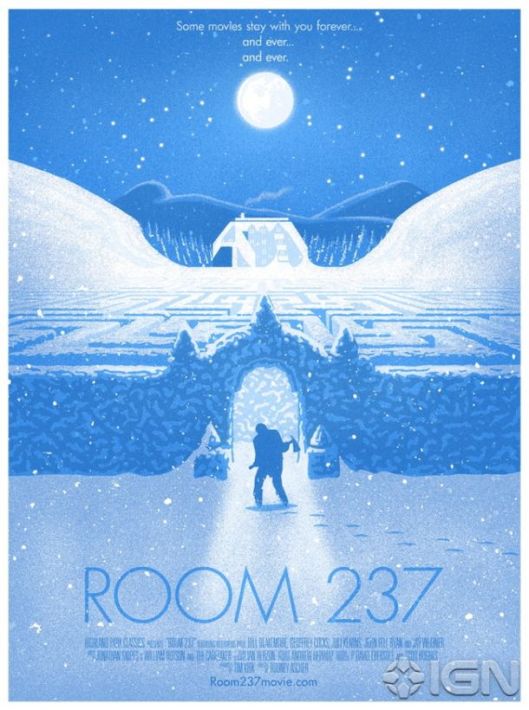

My first negative criticism lies in the absence of us being shown who the people are that are offering their interpretations. I wondered why we were given only the name of each speaker and their audio. Well, a name would seem to be the bare minimum in terms of us being given something to identify the speaker by, and this approach isn’t initially problematic, but it becomes so throughout the body of the film. In breaking up most of the interpretations into little chunks so we are fed different bits of different readings in succession––rather than designating a set time to each individual speaker––director, Rodney Ascher, makes little effort to reintroduce each speaker. The result is a shemozzle of almost indistinguishable voiceovers (gender being the only explicit change) and ideas. As some of the film’s promotional material suggested, Room 237 was to be a complete immersion into a figurative labyrinth of readings and concepts. Yet, it seems that the true labyrinth, at times, is the film’s structure, and the person in the maze is me trying to figure out just who the hell is saying what about which idea. Further to the point, the promo also suggested deep immersion into Kubrick’s picture. But breaking up the interpretations also breaks up their flow in a way that has the readings almost resisting a sense of depth, a tendency compounded by voice-over ambiguity. I’d also be remiss if I didn’t say that the non-diegetic music choices throughout the documentary were similarly problematic. They have distracting and meandering qualities, whose continuity over successions of different interpretations largely contributed to a sense of melding the readings into the confusion described above. I must note here that before seeing the film I was already familiar with the Holocaust thesis of Geoffrey Cocks5 and the Native American genocide reading6, both being thorough works. Seeing how each of these ideas were presented – in disjointed and incomplete forms or those which were not at least well-rounded – made me wonder about a common concern in writing: that is, we may find ourselves reading about a familiar topic only to discover that the writer has, for instance, fudged a conceptual detail. We may then find ourselves becoming suspicious of the text, wondering that if one mistake has been made, how many more might there be?

Misrepresentation:

It was with the same suspicion that I began to think about Room 237, which leads me to my second negative criticism; that is, if I was able to recognise where the ideas I was familiar with were incomplete, then isn’t it now possible that some of the other ideas might have been similarly misrepresented, thus leading to a lack of conviction? Well, okay, the answer here isn’t necessarily ‘yes’, but rather it is ‘maybe’, for it’s worth keeping in mind that it is also possible that a recognised mistake in a work is the only mistake. Some of the ideas may only be conjecture (for instance, the faked moon landing scenario) or mere observations with no deeper significance, and as such may have been chosen to give us a different way of thinking about small aspects of Kubrick’s film. However, the fact remains that perhaps in omitting solid consistency of the ideas being presented––as with the Holocaust and Native American genocide readings––the film gives the ideas, at times, only a diminished chance of being taken seriously. If people watch and think about the arguments, some of which seem to be incomplete, they might conclude that they don’t have enough information to judge the ideas, so they may then decide to suspend judgment. Yet, I think the real danger here is that people might not be prompted to think about the arguments, instead taking them at face value and, due to their incompleteness in presentation, they may feel impelled to disregard the ideas as silly or tedious.

From here, I’m led to wonder who this film is for – maybe not for people who are already familiar with some of The Shining’s interpretations. I’m also led to wonder about Ascher’s intention with Room 237. A common tagline for Room 237 was “some movies that stay with you forever… and ever… and ever”.7 What’s suggested here is a kind of language double-duty: sure, the tagline echoes the utterance of The Shining’s two dead girls, but it also suggests Kubrick’s film being a kind of phenomenal obsession, which has hooked those offering their interpretations. So maybe Ascher’s aim was to convey a strong sense of obsession, or bite-sized tastes of obsession, rather than full-blown close reading or dissertation. As for me, well, I can’t exactly say that I would suggest avoiding Room 237, only that elsewhere there remain clearer and deeper immersions into the phenomenon.

Notes:

1. Rodney Ascher (dir.), Room 237 (Metrodome Group, 2012).

2. Saul Bass, The Shining poster art [image], (1980) <http://www.impawards.com/1980/shining_ver1.html>, accessed Aug. 2013.

3. Stanley Kubrick (dir.), A Clockwork Orange [2008] (Warner Home Entertainment, 1971).

4. Anthony Burgess, A Clockwork Orange (London: Penguin Publishing, 2008), 9.

5. Geoffrey Cocks, The Wolf at the Door: Stanley Kubrick, History, and the Holocaust, (New York: Peter Lang Publishing, 2004). This text is where Cocks’ ideas find there fullest expression, but a succinct yet detailed version can be found in Geoffrey Cocks, James Diedrick, and Glenn Perusek (eds.), Depth of Field: Stanley Kubrick, Film, and the Uses of History, (Madison: University of Wisconsin Press, 2006).

6. Rob Ager, ‘Chapter 12: slavery, cannibalism and genocide’, Collative Learning [webpage], (2008) <http://www.collativelearning.com/the%20shining%20-%20chap%2012.html>, accessed 2011.

7. Aled Lewis, Room 237 poster art [image], (2012) http://au.ign.com/articles/2012/09/19/mondo-poster-debut-for-room-237>, accessed Aug. 2013.

Bibliography:

Ager, Rob, ‘Chapter 12: slavery, cannibalism and genocide’, CollativeLearning [webpage], (2008) <http://www.collativelearning.com/the%20shining%20-%20chap%2012.html>, accessed 2011.

Ascher, Rodney (dir.), Room 237 (Metrodome Group, 2012).

Bass, Saul, The Shining poster art [image], (1980) <http://www.impawards.com/1980/shining_ver1.html>, accessed Aug. 2013.

Burgess, Anthony, A Clockwork Orange (London: Penguin Publishing, 2008).

Cocks, Geoffrey, The Wolf at the Door: Stanley Kubrick, History, and the Holocaust, (New York: Peter Lang Publishing, 2004).

Cocks, Geoffrey, Diedrick, James and Perusek, Glenn (eds.), Depth of Field: Stanley Kubrick, Film, and the Uses of History, (Madison: University of Wisconsin Press, 2006).

Kubrick, Stanley (dir.), A Clockwork Orange [2008] (Warner Home Entertainment, 1971).

Lewis, Aled, Room 237 poster art [image], (2012) <http://au.ign.com/articles/2012/09/19/mondo-poster-debut-for-room-237>, accessed Aug. 2013.